V.

by Thomas Pynchon (1963)

“Rachel was looking into the mirror at an angle of 45 degrees, and so had a view of the face turned toward the room and the face on the other side, reflected in the mirror; here were time and reverse-time, co-existing, cancelling one another exactly out. Were there many such reference points, scattered through the world, perhaps only at nodes like this room which housed a transient population of the imperfect, the dissatisfied; did real time plus virtual or mirror-time equal zero and thus serve some half-understood moral purpose?”

V. is Thomas Pynchon’s first novel, a postmodern maze of settings and plot lines, written almost unbelievably at twenty-six years old. The usual Pynchonian themes are here: paranoia, control, and conspiracy. However, this felt like his most disjointed book out of all the ones I’ve read so far (those being The Crying of Lot 49, Inherent Vice, and Gravity’s Rainbow). It’s not necessarily a bad thing, but there are entire chapters that introduce new characters never to be seen again – one can almost read this as a collection of loosely connected short stories.

We begin on Christmas Eve, 1955, where the first of two main protagonists, discharged U.S. Navy sailor Benny Profane, wanders into a local bar. In the next chapter, British Foreign Officer Herbert Stencil is introduced, as well as his quest for a woman referred to as ‘V.’ in his father’s notebooks. Other characters include (but are not limited to) Profane’s love interest Rachel, her roommate Esther, the NYC artist Slab, and psychologist/dentist Dr. Dudley Eigenvalue. From here, the novel takes us to New York City, Egypt, Italy, Southwest Africa, Malta, and Paris, all at different times in history, loosely connected by the mysterious V.

“Though offering no clue to their enigma; for they reflected a free-floating sadness, unfocused, indeterminate: a woman, the casual tourist might think at first, be almost convinced until some more catholic light moving in and out of a web of capillaries would make him not so sure. What then? Politics, perhaps.”

Unlike Gravity’s Rainbow, which takes place during WWII, this novel deals with the aftermath of said war. But it’s not spoken about directly, save for a comment here or there; it’s shown to us by what happens as Profane, Stencil, and others yo-yo around their lives, looking for meaning, constantly resisting becoming ‘inanimate’ or ‘non-human’ – driven lifeless by the horrors of war. This motif was probably my favorite throughout the book, best personified by the crash-test dummy SHOCK.

“SHOCK was thus entirely lifelike in every way. It scared the hell out of Profane the first time he saw it, lying half out the smashed windshield of an old Plymouth, fitted with moulages for depressed-skull and jaw injuries and compound arm and leg fractures. But now he'd got used to it.”

The slow acceptance, or “getting used to,” of becoming inanimate is what some of these characters attempt (and fail) to resist. Slab’s painting Cheese Danish No. 35, for example, presents a bird constantly eating from the tree in which it resides, never needing to move, as the tree keeps growing, eventually impaling the bird on a gargoyle’s tooth at the top of the painting.

“‘Why can't he fly away?’ Esther said. ‘He is too stupid. He used to know how to fly once, but he's forgotten.’ ‘I detect allegory in all this,’ she said. ‘No,’ said Slab.”

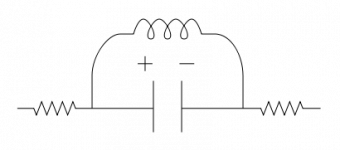

Pynchon also proposes that the WWII ‘Kilroy is here’ drawing originated as band-pass filter schematic, further solidifying that in war we are ever so close to being mechanical and inhuman. Fortunately, the antidote to this “non-humanity” is alluded to – individuality. In “Chapter 11: Confessions of Fautso Maijstral”, we follow multiple versions of Fausto before, during, and after the WWII siege of Malta, each version exhibiting differing levels of humanity. Tragic events bring him to an almost inanimate existence, but the slow process of living and consistently being himself brings him back.

"Mathematically, boy," [Eigenvalue] told himself, "if nobody else original comes along, they're bound to run out of arrangements someday. What then?" What indeed. This sort of arranging and rearranging was Decadence, but the exhaustion of all possible permutations and combinations was death.

But V. is also upfront about the discomforts of war, particularly “Chapter 9: Mondaugen’s story.” Just like in Gravity’s Rainbow, the genocide of the Herero population plays an important part to the story, but in V., there is a more graphic depiction from the point of view of the Germans. It’s rough. Not just because this is something that is lost to history (the first I’ve heard of this genocide was during my GR read), but it’s from the point of view of the white Kurt Mondaugen. However, because it’s from his point of view, it allows these horrors to be portrayed ethically; if Pynchon decided to write this story from the Herero point of view, that would be silencing and appropriating their voice. I can’t explain it any more eloquently than this quote from Ariel Saramandi, Editor-in-Chief of Transect Magazine, from her excellent article Thomas Pynchon Shows Us How White Writers Can Avoid Appropriation:

“…you see the genocide unfold through Mondaugen’s eyes, the reader feels like a witness, hands tied and somehow complicit in the mechanisms of white history. Indifference is impossible. The colonists’ actions are told in the same, detached voice as the German reports, a voice that showcases the utter, systemic dehumanization of the Hereros…”

V. is tough, and it wouldn’t be my suggested starting point for reading Pynchon. The connections are harder to find, but following a Reddit reading group, with summaries and analyses after each chapter, was actually pretty fun – I love hearing what others take away from their reading. The historical events being used as a backdrop for the overall themes kept me engaged throughout, as well as rooting for Profane and Stencil to (hopefully) find what they’re looking for.

“Hitler, Eichmann, Mengele. Fifteen years ago. Has it occurred to you there may be no more standards for crazy or sane, now that it's started?”