by Thomas Pynchon (1997)

2024 reads, 17/22

“Snow-Balls have flown their Arcs, starr'd the Sides of Outbuildings, as of Cousins, carried Hats away into the brisk Wind off Delaware,-- the Sleds are brought in and their Runners carefully dried and greased, shoes deposited in the back Hall, a stocking'd-foot Descent made upon the great Kitchen, in a purposeful Dither since Morning, punctuated by the ringing Lids of Boilers and Stewing-Pots, fragrant with Pie-Spices, peel'd Fruits, Suet, heated Sugar,-- the Children, having all upon the Fly, among rhythmic slaps of Batter and Spoon, coax'd and stolen what they might, proceed, as upon each afternoon all this snowy December, to a comfortable Room at the rear of the House, years since given over to their carefree Assaults.”

The textual equivalent of a cinematic long take, the first sentence of Mason & Dixon sets the stage of the story into which you are about to embark. On a cold December evening in 1786, Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke sits down with the children of his family and commences an epic retelling of the lives of astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon. Already, we’ve got two levels of narrative: Pynchon, the author, is relaying to us the Reverend’s retelling of the history of Mason and Dixon, and on a greater level, the birth of America. It’s a fitting book to finish this past Independence Day weekend.

What is History?

Within the Reverend’s retelling, however, he is noticeably absent from most of the events with Mason and Dixon, only crossing paths with them a few select times when they are not travelling together in America. So, how do we know that the Reverend is relaying an exact story, down to the exact dialogue? How do we know that Pynchon is communicating the Reverend’s exact story? The narrative framing of M&D brings us to the first major theme: what is history, who tells it, and how we can trust what we learn about the truth of America’s past?

“History is hir'd, or coerc'd, only in Interests that must ever prove base. She is too innocent, to be left within the reach of anyone in Power,— who need but touch her, and all her Credit is in the instant vanish'd, as if it had never been.”

While M&D is rife with accurate historical fiction, Pynchon also fills this book with anachronistic references to Star Trek, Doctor Who (“the stagecoach is bigger on the inside than the outside!”), and other future events. Maybe it’s all just fun for us readers of the modern era, but on a deeper level, is Pynchon saying that history is continuously doomed to repeat itself?

For now, let’s put aside the fact that history is interpreted and retold, possibly by those with an agenda. What happens in M&D? Why should we believe what the Reverend (or Pynchon) tells us?

Brutality Uncheck’d

In the first section of the book, Latitudes and Departures, Mason and Dixon stop at Cape Town, South Africa on their way to observe the Transit of Venus. Here, they are horrified to see how the Dutch colony treats their slaves, raising the question early on: what happens when colonialists are given unrestricted power, out of sight from the laws that govern them? I’m sure you can tell where I’m going with this, as it’s in the middle section, America, we see this lawlessness continue as Mason and Dixon set sail toward America in 1763.

“The long watchfulness, listening to the Brush. Ev'ry mis'rable last Leaf. The Darkness implacable. When you gentlemen come to stand at the Boundary between the Settl'd and the Unpossess'd, just about to enter the Deep Woods, you will recognize the Sensation”

Upon reflection, I really appreciated this first section: not just for foreshadowing the colonialist regimes in early America, but also getting to know our main characters before traveling west. To be honest, their personalities and dialogue reminded me of Crowley and Aziraphale from Good Omens: Mason, ever so depressive and gothic, recovering from the death of his wife, while Dixon being wide-eyed and optimistic, happy to work with Mason and go on this journey together.

Ghosts of America’s Past

After smoking a joint with Colonel George Washington, and drinking some ale with Ben Franklin, our two protagonists set off westward from Philadelphia (“a Heavenly city and crowded niche of Hell”) to create the boundary that today defines the border between Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware.

“They saw Brutality enough, at the Cape of Good Hope. They can no better understand it now, than then. Something is eluding them. Whites in both places are become the very Savages of their own worst Dreams, far out of Measure to any Provocation.”

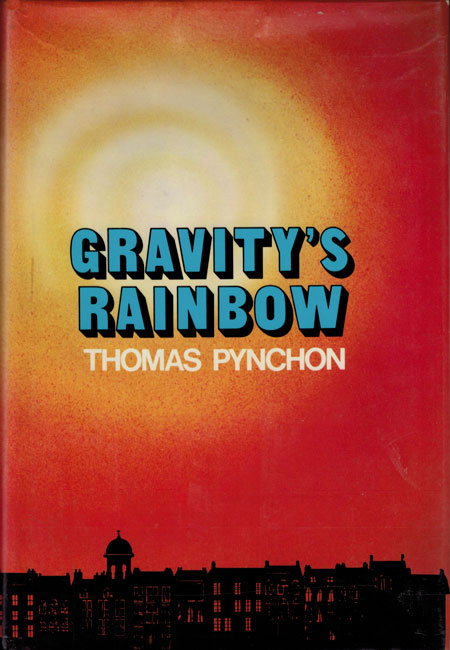

The colonialist tendencies mentioned above noticeably continue in this section, as they arrive just after the Paxton Massacre. Like the Herero genocide in V. and Gravity’s Rainbow, it makes for uncomfortable reading, even if our main characters aren’t actively involved in these travesties. When Dixon wonders (absentmindedly) to a group of Native Americans if they are in any danger in America, a Mohawk chief responds: “‘Yes of course you are in danger. Your Heart beats? You live here?’ gesturing all ‘round. ‘Danger in every moment.’”

Throughout the novel, there’s also this constant examination of man-made and natural borders, and more importantly, the consequences as to when these artificial boundaries are imposed in our natural world; the biggest example of course is the Mason-Dixon line itself. This border separated the free northern states from the southern slave states, with consequences for years to come. M&D uses this example among others to ask us about the consequences as humans try to fight against the “natural order” of things, and I’m reminded of the concept of “desire paths,” where again, imposed boundaries are no match for human nature — this theme throughout the book was one of my favorites to think about.

“Mason groans. ‘Shall wise Doctors one day write History's assessment of the Good resulting from this Line, vis-à-vis the not-so-good? I wonder which List will be longer.’”

Mystical Beings of Control

Much like history herself, this book is veiled in a fog of uncertainty, the narrative always slightly out of focus. And with this, we get to the theme that pervades throughout all of Pynchon’s work: control. But in an age where the highest form of technology is represented by John Harrison’s marine chronometer and a mechanical digesting duck , the “shadowy technocratic forces” that I’m used to seeing in Pynchon’s other books must resort to a more primitive means of control – and what was more controlling at the time than religion?

“If Chimes could whisper, if Melodies could pass away, and their Souls wander the Earth...if Ghosts danced at Ghost Ridottoes, 'twould require such Musick, Sentiment ever held back, ever at the Edge of breaking forth, in Fragments, as Glass breaks.”

These sinister back-room societies emerge from the shadows just enough to steer our heroes under the guise of “free will,” withholding a kind of necessary gnosis from them. And it’s not just the Catholic church that has the invisible hand: the mystic arts play their own key role, as ley lines pervade their voyage, Jesuits control their messages, and forest creatures such as golems and fairies all surround our two characters. As they explore caverns, temples, and mountains, I could imagine a soundtrack of Gregorian chants in the background – or even Enya.

Religious allusions pervade their entire quest throughout America, as their journey is compared to the Stations of the Cross – some scholars even suggest that their daily morning cup of coffee is one of the blessed sacraments. These allusions had me doing a deep dive into religious mysticism, the occult, and other fantastical beings. Some are harmless, such as the TARDIS-like stagecoach or ghastly visits from Mason’s deceased wife. But remember when we put aside the fact that history is told to us through someone else’s rose-colored lens? M&D leads me to believe that these theocratic forces were the ones ultimately controlling not just Mason and Dixon, but steering America down the wrong path from the very beginning.

“Hell, beneath our feet, bounded,— Heaven, above our pates, unbounded. Hell a collapsing Sphere, Heaven an expanding one. The enclosure of Punishment, the release of Salvation. Sin leading us as naturally to Hell and Compression, as doth Grace to Heaven, and Rarefaction.”

Where is She Now?

The dynamic duo returns to England in the third section of the book, Last Transit. This section is more of an epilogue, filled with hypnagogic expository and much less “action” overall, which I think works really well after reading 700 pages of misadventures. It’s in this section that the true friendship of Mason and Dixon blooms, something that you realize was growing the whole time – I can see why people say that Pynchon’s later works showed a lot of character development, as this last section was heartening and bittersweet at the same time.

If you are interested in reading this one, know that M&D is written in 18th century style English (as you've probably surmised from the quotes above), even though it was published in 1997. This took some adjusting when I started reading, but it really helps with immersion, making you feel like you’re reading an actual primary source re: the travels of the Reverend, Mason, and Dixon. And even though M&D is set in the 1700s, it is still incredibly relevant centuries later. Are there still invisible hands at play, pulling our strings under the guise of free will? Are there still colonialist tendencies, patriarchal hierarchies, and systemic racism? I'll let you answer that yourself.

“Does Britannia, when she sleeps, dream? Is America her dream?— in which all that cannot pass in the metropolitan Wakefulness is allow'd Expression away in the restless Slumber of these Provinces, and on West-ward, wherever 'tis not yet mapp'd, nor written down, nor ever, by the majority of Mankind, seen,— serving as a very Rubbish-Tip for subjunctive Hopes, for all that may yet be true,— Earthly Paradise, Fountain of Youth, Realms of Prester John, Christ's Kingdom, ever behind the sunset, safe till the next Territory to the West be seen and recorded, measur'd and tied in, back into the Net-Work of Points already known, that slowly triangulates its Way into the Continent, changing all from subjunctive to declarative, reducing Possibilities to Simplicities that serve the ends of Governments,— winning away from the realm of the Sacred, its Borderlands one by one, and assuming them unto the bare mortal World that is our home, and our Despair.”

#readingyear2024 #american #history #postmodern #physicallyowned #pynchon