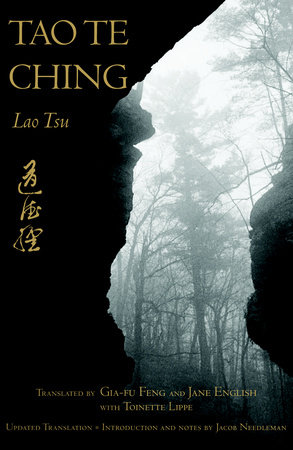

Tao Te Ching

by Lao Tzu (~300 BC)

2025 reads, 3/25

“Empty yourself of everything. Let the mind become still. The ten thousand things rise and fall while the Self watches their return.”

How does one even review the Tao Te Ching? It's like reviewing the Bible, as it’s infinite interpretability and historical endurance situate it as one of the most translated texts in world literature. Thousands of scholars and philosophers have written thousands of essays, analyses, and translations. So, after one measly read through of this foundational text in Taoism, what does a white guy from New Jersey have to add?

Nothing.

But although I’m no scholar on Taoist thought, Eastern philosophy, or literally any sort of humanities discipline, I can talk about my experience reading it. First, and I think most will agree, that I find it odd to call Taoism a religion, at least not how I think of one in the traditional WASP sense: church services, prayers, commandments, bread & wine. I find this much more introverted, contemplative, philosophical – a way of life, if you will.

“The space between heaven and Earth is like a bellows. The shape changes but not the form; The more it moves, the more it yields.”

And as with any philosophy, I cannot just read the Tao Te Ching and call it a day. I need to think it and live it. And although I started reading it last year, absorbing it bit by bit while I have my morning tea, I’m certainly not there yet; but I have the physical book, and I’m going to do my best to go back to it when I can.

So maybe this wasn’t really a review, maybe this was more of a personal reaction. The four stars don’t really mean anything. (Do numerical reviews ever really mean anything?) It’s short enough to check out yourself, too: I enjoyed the translation I have, the one by Gia-fu Feng and Jane English – supposedly it sacrifices some intricacy in exchange for straightforward prose that cuts to the essentials of the original (and you can even find it online).

“The Tao begot one. One begot two. Two begot three. And three begot the ten thousand things.”